The starting point for great Moulin-à-Vent is some old Gamay vines – 30 years will do it. Oh, and 300 million years to prepare the soils. Turning volcanic granite into stones and sands takes time! These are some of the oldest soils in France. It’s a striking sight, a pink tone from the granite and iron oxide, with a sparkle of silica that reflects light into the vines. Edouard Parinet, owner of Château Moulin-à-Vent in the heart of this Beaujolais Cru, explains to me looking down at the soil, “you don’t want to compact this soil and see it skimmed away in the rain, it takes 30 million years to replace one centimeter!”.

The drive from Beaune takes me down the A6, the feeling already “south” long before Macon, but still a Burgundy feel. As I exit just below Macon, turning southwest, there is still familiarity – here we have the Jurassic clay-limestone of Pouiily-Fuissé planted mostly to Chardonnay. And then things change quite dramatically – valleys, and along the ridge lines, pudding bowl hills of pink granite, and – still often a sight here – bush vines of Gamay. We are now as the eastern limit of the volcanic part of the Massif Centrale.

In cultural identity we are at a crossroads – the Rhône, the Loire, and Burgundy all have departmental claims to parts of Beaujolais. In the wines too all three can be felt at times – the warmth and generosity of the Rhône, the freshness and vibrancy of the Loire, and the fineness and detail of Burgundy. At a serious domaine here you can find these sorts of expressions – it depends on a few things, which I’ll come to. As wine enthusiasts we are discovering all this anew, really, as Beaujolais reinvents itself.

Gamay grown here can lend itself to a very jolly sort of wine, unserious, “glou-glou” wine. Easy wines for picnics, and anytime drinking. The most extreme form is Beaujolais Nouveau – sharp skinny pinkish wine sold, and consumed a few short weeks after harvest. In the ‘80s this stuff was marketed so well it became synonymous with the region, and with inconsequential quaff. Great! And also terrible!

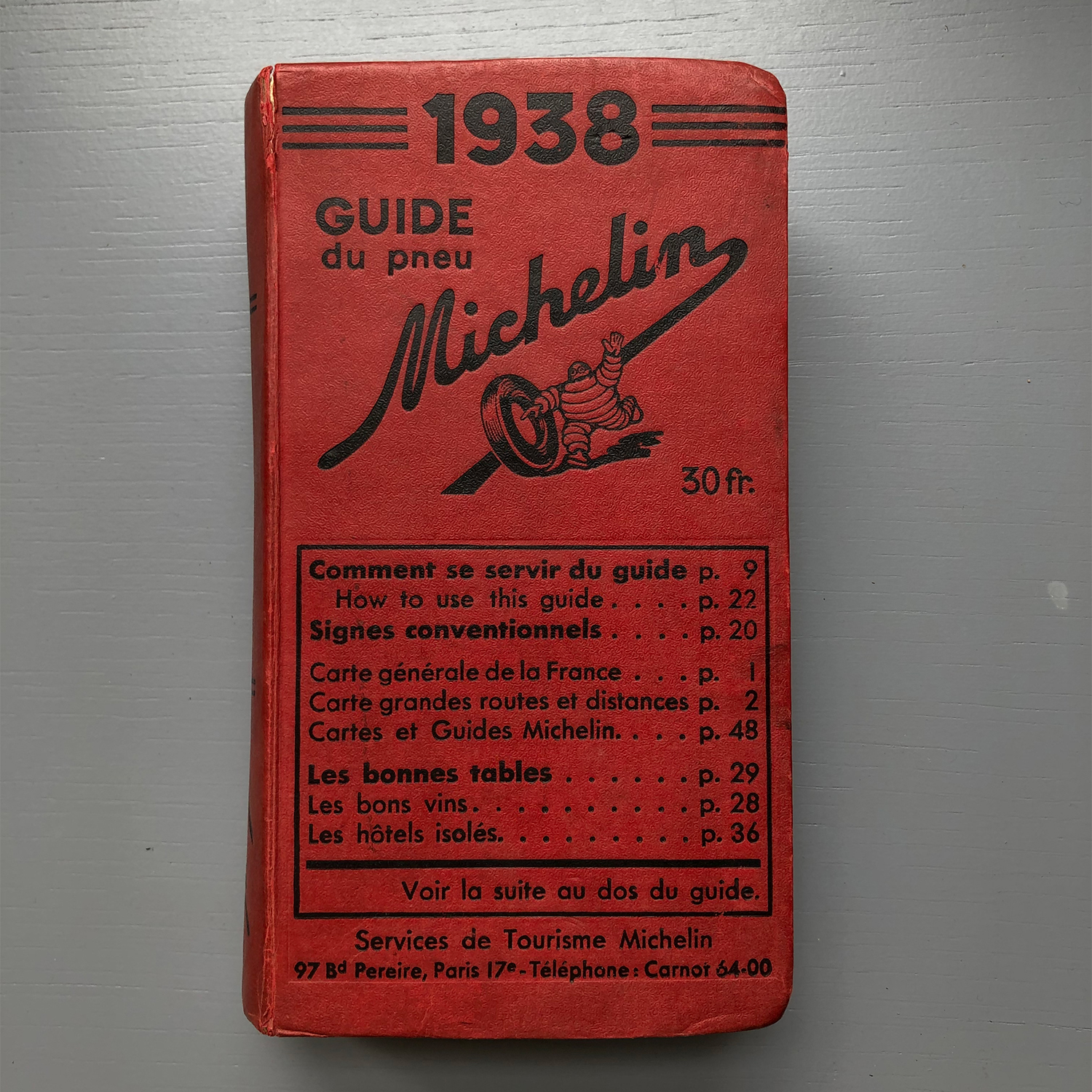

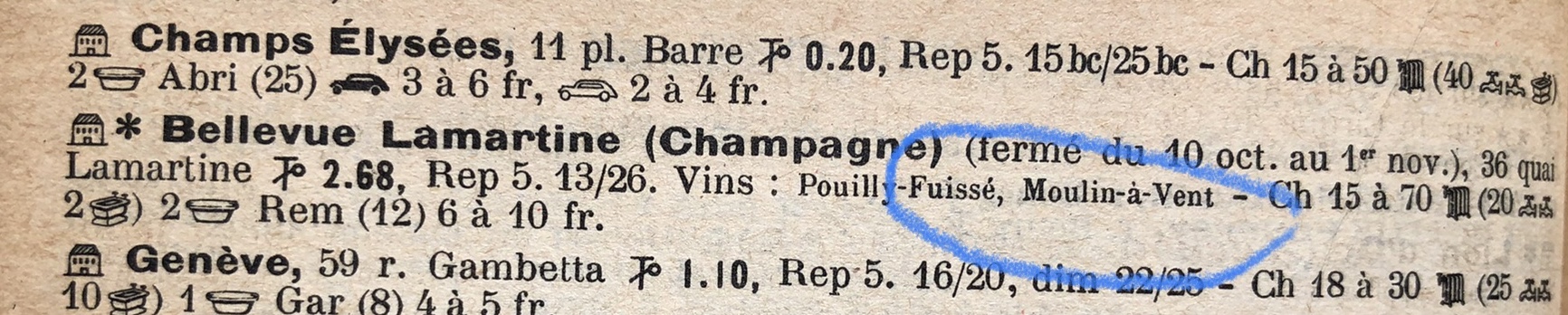

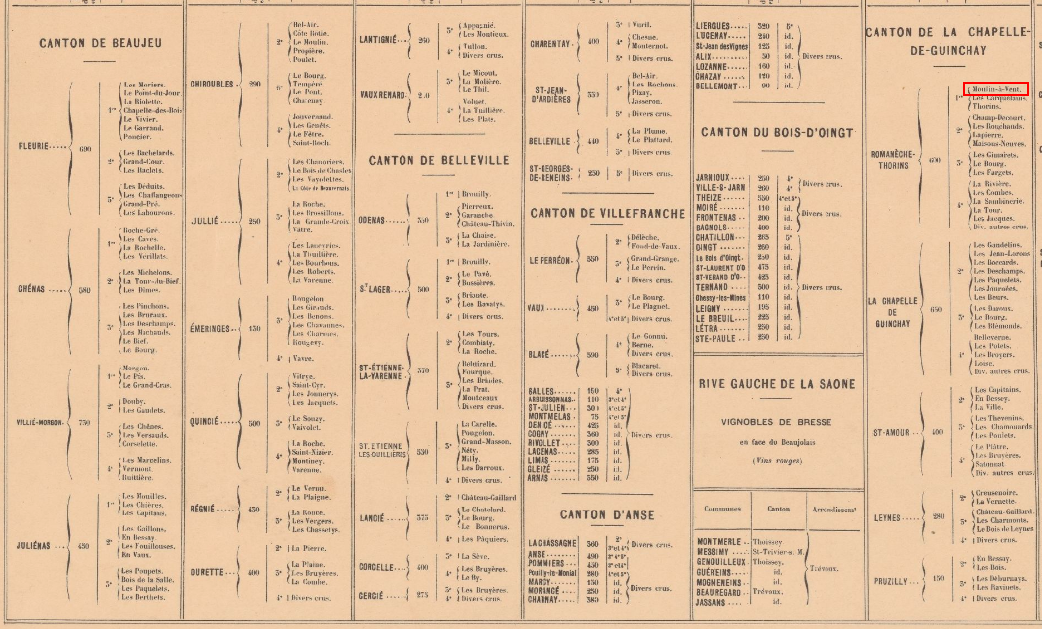

It became hard to imagine just what a mighty reputation the top wines of Beaujolais had a century or so ago. The top Crus – like Fleurie and Moulin-à-Vent – featured (without mention of Beaujolais) alongside names likes Clos Vougeot and Hermitage on grand dinner menus, with prices on retail lists not so far below. My wife’s 1938 Michelin Guide to France includes ‘Moulin-à-Vent’ and ‘Fleurie’, as featured wines at temples of gastronomy, without mention of ‘Beaujolais’. Fine diners of the day knew.

In 2009, when Parisians Jean-Jacques Parinet and son Edouard purchased the Château du Moulin-à-Vent, all this had been lost to history however. How then to rebuild a quality wine estate and an image to match?

A conscious choice was made to omit the wider appellation – Beaujolais – from any branding or communication. The Château du Moulin-à-Vent makes Moulin-à-Vent.

The focus was to draw attention to the way a single qualitative grape can translate individual terroirs. In other regions it’s the way those who find pleasure in learning what different places can bring in expression are lured in. It’s the language of Barolo crus, Mosel grosse lagen, and Burgundy climats. In Beaujolais’ AOC rules there is no classification to fine tune things beyond the name of the Cru – e.g. Moulin-à-Vent – though vineyard names can be put on labels, but there is no classification for them.

In the 19th century that detail was there in Beaujolais. Antoine Budker’s extensive study of Beaujolais vineyard terroirs led him in 1869 to publish his ranking of the individual lieux-dits (vineyards) from 1st growth to 5th growth. While some of today’s Beaujolais Crus see saw their best vineyards only reach Budker’s 2nd class, the greatest concentration of 1st growths were in today’s Moulin-à-Vent and Fleurie AOCs.

Edouard takes me up in his 4x4 to the ridgeline of Fleurie, and we stand at the top of the Poncié vineyard – a Budker first growth – to survey the scene below. “Between this ridge line and the one beyond lie many of Budker’s top vineyards”. Moulin-à-Vent lies like an amphitheatre between, sloping and sweeping eastward toward a tree line and the plains below. In the centre, at Les Thorins, sit the Château du Moulin-à-Vent and the eponymous windmill.

Moulin-à-Vent from Fleurie's Poncié vineyard

The estate wine at Château du Moulin-à-Vent is a blend of vineyards that combine to represent the Cru and the estate – Aux Caves (Budker 1st growth), Le Moulin-à-Vent (1st), Les Vérillats (1st), La Rochelle (1st), and Champ de Cour (2nd). (The latter three are also single vineyard wines in the château’s range). Edouard and I visit two of them. At Aux Caves there is a special section flanked by a line of silica-rich granite. It’s warm and dry enough that I can see a patch of cactus growing! The soil is sandy granite, very poor, rich in silica. “Here we make a our special cuvée, Grands Savarin”. We drive down slope to Champs Cour, and the soils thicken, and turn whiter. “The ancient influence of the water is here - these are not the colluvium soils we saw before – these are alluvium white clays, and protected from the wind”.

Cactus growing wild at Grands Savarins

Back at the château I taste the full range of wines here from 2020 – a ripe, balanced and very promising vintage. I often have a real soft spot for ‘Champ de Cour’ – it is often the most floral, fresh, and at the same time fleshy, and fruity of the single vineyard bottlings. Alongside the estate label, it is the most accessible when young. It sits in contrast to the intense and brooding ‘Les Verillats’, to my palate often the most brooding, concentrated and intense expressions of Moulin-à-Vent at the estate. It is an especially wind-swept vineyard, a factor that concentrates and intensifies the fruit, and decreases the ratio between juice and skins. It also – for me – often has more of Gamay’s licorice note. In ‘La Rochelle’ I feel the refinement, fine structure, and orientation toward small details. To me it's very grand cru, and it really benefits from some time in cellar to soften its fine, mineral frame. When you speak to Jean-Jacques (who I can attest is a great cook) about La Rochelle there is a twinkle in his eye – “this and a braised shoulder of lamb?....” (he rolls his eyes in pleasure). ‘Les Grands Savarins’ is often the most aromatically “wow” wine in the range. It’s partly the poor soil and warm site, and partly the winemaking offset, a high proportion of whole bunch fermentation – it can have so much appeal when young, but deceptively so. Finally ‘Clos de Londres’, a small walled vineyard adjacent to the château, is almost the opposite Grands Savarins – brooding and potent, packed with fruit and power, it can be awkward young, but in this solar 2020 vintage, it seems meltingly intense and attractive, a long haul wine not yet closed up.

Granite, silica, iron-oxide and manganese, with ancient weathered sands,

at Grands Savarins in Moulin-à-Vent with Edouard Parinet.

I enjoy each of these single vineyard cuvées in the same way I do in the Mosel, Barolo and Burgundy – like five siblings from the same family. Each one brings its own personality, and can play to different dishes, occasions or moods. That, and the vintage interpretation each terroir brings each year make further exploration a rewarding experience.

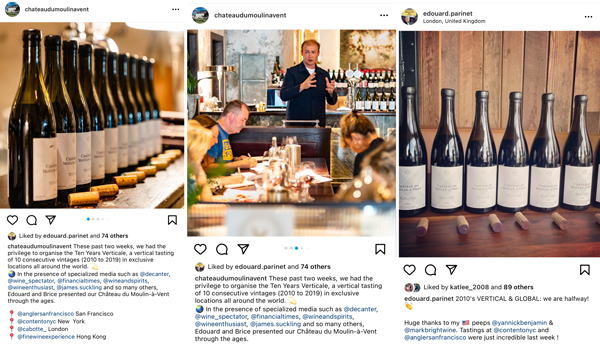

The estate cuvée – the Château du Moulin-à-Vent ‘Moulin-à-Vent’ – is the amalgam of all of this, in one wine. It’s the standard bearer. As such, it’s this cuvée with which the Parinets chose to mark their first decade, with a vertical tasting. Actually four consective verticals, around the world. Edouard Parinet has something of the young Mondavi, Gaja, or Loosen about him – more introverted perhaps than those three, but like them, acutely aware that the case that has to be made is not just that of the estate’s, but also of the appellation, and the ”Gamayzing” Gamay grape. It needs to be explained, communicated, and in the age of Instagram.

Edouard hosted the tastings of ten consecutive vintages – 2010-2019 – of the estate cuvée in person in New York, then San Francisco, then London (which I attended), and then Hong Kong (which The Fine Wine Experience and Bâtard restaurant hosted, and Edouard and I joined by Zoom).

So, what did I find?

Moulin-à-Vent, and in particular the Château du Moulin-à-Vent suffers from competing expectation and reputation. Gamay is a jolly grape, and when I navigate the map between the relative delicacy and finesse of the Côte d’Or’s Pinot Noirs to Beaujolais’ north, and the power, structure and richness of the Northern Rhône’s Syrahs to Beaujolais’ south, Beaujolais can straddle the two style-wise (depending on sunnier or cooler vintage), but we tend to demand of Beaujolais a very friendly, drink-young, soft, fruity and round sort of wine, one that Gamay can offer. This expectation has been compounded during the hot-air-balloon-race-to-deliver-the-Beaujolais-nouveau generation of drinkers of the ‘80s and ‘90s.

Yet, at the same time, the classic reputation of Moulin-à-Vent – reinforced by Budker’s research – is that at the quality apex, the wines are highly ageworthy… and by extension, reward cellaring.

It’s no surprise then that, as Parinet’s task is at once to convince us of the “Gamayzing” pleasure Moulin-à-Vent can deliver young (even very young), it is also to convey that here is a wine that deserves and rewards some cellaring, something the vertical tastings emphasized.

The estate cuvée straddles the line deftly. Tasted young within the range of cuvées from the château, it is the most open and easy to appreciate. Yet, cellared it can still reveal more, as this vertical showed. Surrounded by UK journalists at the London vertical at Cabotte, I heard one remark, offered somewhat in surprise, “there’s a remarkable consistency of colour here. None has turned brown.”

You can find my full tasting notes from this tasting below.

The vertical demonstrated the consistently high quality of the wines, particularly in vintages that brought great challenges, like 2017. Manual harvest in small cases, and careful sorting of fruit at the winery can be felt in a year like that. The tasting also displayed an evolution in approach, and the progress in their work. No doubt the improvements in farming, the conversion to organic viticulture, and the development of a massale selection programme are, and will all pay dividends. The arrival of winemaker Brice Laffond in 2013 can also be felt. The wines have become more tender, more transparent than the excellent but very solid 2010. Laffond will adjust the proportion of whole bunch fermentation depending on the vintage conditions, and the needs of each cuvée, and this adjustment can be felt particularly in solar years like 2018.

For all that, while Parinet’s choice to show the estate cuvée in a vertical was the logical one, the Château du Moulin-à-Vent ‘Moulin-à-Vent’ is the cuvée I personally usually prefer to drink younger, within the range. It’s the most accessible young – I wouldn’t hesitate to drink the 2019.

To cellar, I enjoy seeing the different expressions of the terroir in the single vineyard cuvées. At lunch at the estate we had a 2019 La Rochelle (94), and it was utterly beguiling, low in acidity, with gushing melting fruit and flavour it offers so much pleasure now, but also has more stuffing – more potential for cellaring than the light and cheerful 2019 estate cuvée.

The natural variation of vintages too can show Moulin-à-Vent’s unique personality and breadth of expression. At the end of the Hong Kong tasting at Bâtard my colleague François Tran asked our guests which wines they liked the most. The top three were 2015, 2016, and 2018. That’s a good a place to start your own exploration as any I think, and I would encourage you to explore across the cuvée range (the favourite wine of the lunch was the 2018 Grands Savarins). We have a great selection in stock from our reserves, from 2019, 2018, 2016, 2015, 2014, and late-released 2010 and 2009, as well as a few magnums and jeroboams.

Many thanks to Edouard Parinet for including The Fine Wine Experience and Hong Kong in his global celebration of the first decade. We look forward to the next.

A fresh sunny vintage, cool and classic, harvested from 26th September, 26hl/ha, it was austere when young.

Still a fresh garnet with a touch of colour development at the rim; a sweet and spicy nose, pomegranate, good freshness and lift; ripe on the palate with concentration, a round texture of fruit and fine bright ripe acidity, this is bold and buoyant, with fine structure. There is a touch of gloss here coming from the high proportion of new oak masking some details I feel, but this is a delicious wine. 91

A very hot and dry vintage that led to an early harvest from 29th August, 36hl/ha.

Clear, though a touch lighter than the 2010, fresh rim; fresh sappy fruit on the nose, a cool and bright tone, brush-herbal notes, this has some savour now; juicy on the palate, lighter weight than the ’10, with an appetizing savoury flavour offsetting the lightweight fruit. A medium to lightweight Moulin-à-Vent for drinking now / drinking up. It doesn’t have the length of the best of them, but it does still have nice fruit. A tasty finish with a crunchy edge. Pleasant, but not the richness, nor the complexity of the best. 89

A wet vintage beset by problems with mildew, harvested from 13th September, double-sorting was required to avoid poor berries, 16hl/ha.

Garnet with a broad light rim showing full maturity; cool and savoury on the nose, an appetizing aroma, some florals too – complex; ripe, savoury, mid-weight, there is some austerity to the tannins, but with plenty of flavours. This is sapid, lip-smacking and layered in flavour. It demands food, but has satisfying sap and complexity. Ready to go now, drink up. 90

A cool, windy spring led to late but even flowering, and a good summer led to a late harvest from 28th September, 25hl/ha. This was the first vintage in organic viticulture and marked the arrival of winemaker Brice Laffond.

Light garnet with a fresh rim; fresh and vibrant on the nose with some savouriness; plump and juicy on the palate, a touch of licorice and savour, moderate length, with a tight, more slender mouthfeel, drying a little perhaps. Nice, moderate weight and flesh, drinking well. 91

North winds slowed development during spring, but summer was beautiful and regular. Harvested from 9th September, 27hl/ha.

Fresh clear colour of mid-depth; fruity, cool and savoury on the nose, a touch floral; a juicy, vibrant frame, though this has a distinct earthiness too; high acidity on the palate, some herbal flavours, starting to dry a touch on the finish. There is some complexity here, and it is quite savoury in style. Good length and fine tannin. Drink now. 90

Low rainfall in spring was followed by a very hot summer, with warm southerly winds keeping the vineyards clean, maturity came fast and harvest began on 27th August, 27hl/ha. This was the first vintage in which some proportion of whole bunches were included in the fermentation with the goal to slow down extraction and sugar release. 2015 saw the beginning of the estate’s own massale vine selection programme.

Clear and with a fuller colour; bright and spicy nose with a licorice note and macerated fruits – this is a more solar year, clearly; rich fruit on the attack, this is concentrated and mouthfilling and at the same time with good acidity; there’s a density of fruit here – some oomph for the long haul, though its great on its fruit right now. There is also some of that Moulin-à-Vent structure, there is tannin here, and it points to food for this vintage. It’s not “glou-glou” wine. Licorice, spice and juicy fruit on the long finish. 92

A humid spring brings vigorous plant growth and leaf production, making trellising work key. Flowering was long and late, and there was some damage from hail. Until the end of July morning dew maintained moisture in the vineyards, August saw heat and drought, and winds kept things clean. Harvest from 20th September, 30hl/ha.

Fine clear ruby-garnet; lovely nose, fresh and fragrant, a floral edge, a complex aroma; beautiful fruit on the attack, there’s a freshness in the expression, lovely friit-acidity-sap tension, it melts gently on the palate and the texture is silky. This for me is the star wine in the vertical – the freshness, complexity, melting texture and juiciness, all with subtle details offered along the way. There is stuffing here too, and the fine tannins are well-covered by sappy fruit. Very good. Now –2036. 93

Bud-break and flowering were early. On 10th July, the first day of veraison (grape skin colour change from green toward purple) there was an almighty hailstorm – 120km/hr winds brought 1cm hailstones in to shred the vineyards in a matter of minutes. A hot dry July and August allowed for the beginning of elimination of damaged berries, some of which simply dried and fell off the vines. Double sorting at harvest, from 6th September, just 12hl/ha.

Mid-light colour, a weaker rim; nice fruit on the nose, pomegranate, a touch of leaf, floral, a lighter, less grand nose after the ’16; fresh, lighter weight on the palate, but this is also spicy, herbal, quite ‘amare’ in that combination of bittersweet herb and orang rind fragrance on the palate. This is fully evolved now, attractive and ready. Just a touch of dryness on the finish where the fruity dries in tone too. Drinking well still but drink up. 88

A very humid spring with mildew challenges, then ‘la fleur a coulé’ giving long, loose clusters with millerandage (berries of different sizes and ripening rates), giving the potential for extra concentration. A very hot summer with low rainfall lead to the loss of malic acid and the concentration of tartaric acids, the juice in 2018 is rich and powerful. Harvest from 31st August, 34hl/ha. Proportion of whole bunch fermentation increased this year.

A vibrant fresh colour, clear with a touch more blue in the tone of the ruby rim; a sweet nose, a bit more confit in the fruit expression; cooked fruits spice, sweetness on the nose; on the palate this ’18 shows a bolder, denser fruit with licorice and dark fruit flavour, spice, and a leather note. Bold and spicy Moulin-à-Vent from a hot year. There is a little warmth and chewiness here too, with a licorice and dark fruit finish. A denser wine, with good acidity, aniseed bittersweetness. This is a hearty, food-friendly wine. Now – 2028. 91

The sunniest vintage since 1990, yet August was cooler than average, a millerandage year that began a little later than usual, 11th September, 25hl/ha.

Fresh, a lighter colour, bright, with a lighter rim and less depth of colour than many of the vintages here; a cool and fresh aroma, crunchy fruit; lighter style on the palate, red fruits, a warm but not hot finish, there is lower acidity here too. Overall this is a lighter depth Moulin-à-Vent, it doesn’t have the flavour depth or complexity of some vintages, but the red fruit and star anise profile to the palate expression is lingering, fresh and refreshing. This – the youngest wine today – is also one of the most open and ready to drink examples. It doesn’t have the stuffing for long ageing that some vintages possess, but it has a nice balance, a melting low acid soft tannin texture and moderate length. 90