© Linden Wilkie, October 2018

Briefly, as we lifted each of the five glasses to our noses and lips we were taken back exactly one century to the time when the grapes were picked. Faded, but agreeable scents, and delicate liquids echoed the memory of that extraordinary month, the final violent convulsion in a four year wholesale campaign set to tear civilisations apart. One that succeeded. A young generation had been ‘lost’ to war, killed, disabled, shocked, lungs poisoned, limbs lost. And heaped upon the tumult, an influenza epidemic so deadly – perversely afflicting in particular this same young generation – that comparisons were drawn to the Black Plague. Five glasses offered beyond the grave, testament to the fact that in the midst of unimaginable misery, the sun still rose, grapes still ripened, and good wine made. Wine that could at least whisper its story to us a world away in time and place.

A group of wine enthusiasts in Hong Kong were deciding what to drink at the next gathering – 28th September 2018. With deep cellars and ambitious an idea, one, two and finally all five of what today comprise the five First Growth red Bordeaux of the 1855 classification had been assembled, all from the 1918 vintage. Even for such a group and in so wine-indulged a city as Hong Kong it was a special moment. I was lucky to participate.

Regular drinkers of older vintages can usually put decades-old vintages into some kind of imaginative context – years like 1961, 1945, and even 1928 stretch within the realms of imagination and experience. But 1918 slips beyond the mind’s horizon, I think for a few reasons.

First, we associate these five estates with some of the great dynasties of ownership and management of the 20th century, but most came after 1918. Indeed the 1918 vintage marks the end of a dynastic era in wine, and in so much else in European life. The dynamic Baron Philippe de Rothschild was to arrive in 1922, transforming Château Mouton-Rothschild, the wine and the image, finally seeing it elevated to First Growth in 1973. He reigned at Mouton for 65 vintages. The owner of Château Haut-Brion, Jacques-Norbert Milleret was killed in action in 1918, the denouement in the Larrieu family ownership story. Haut-Brion’s renaissance, aligning generations of Dillon owners and Delmas régisseurs would begin in 1935. The end of World War One would also usher in the great Woltner family era across the road at La Mission Haut-Brion. At Château Margaux the war drained the fortunes of the Pillet-Will owners, who sold in 1920. But today we recall the peak and then slow fade of the Ginestet ownership (from 1934) and the renaissance under the Mentzelopoulos family (1977-). The “Pillet-Will” name stands as a mere footnote due to the fame of the 1900 vintage, and without that it would slip altogether from contemporary oenophile consciousness. The Rothschilds at Lafite could withstand the shock, and the sound leadership of Hubert de Beaumont and the good management of régisseur Daniel Jouet at Château Latour saw continuity there provide the exceptions. So heavy was the weight of crisis that is was estimated some 20 great châteaux were sold at the end of the war, between 1918 and 1920.

Pack horses taking ammunition to front at Vimy Ridge, April 1917. (Library & Archives Canada, PA-001229)

We think of the war on its bloody muddy fronts, but the 1918 vintage provides a snapshot of its impact on rural enterprise. Horses were not a choice like they are today, they were essential for vineyard work. Many were requisitioned, sent to bear the heavy loads of war matériel. They became very expensive and difficult to acquire. Many men and women joined the machine of war, and there were labour shortages in the vineyards. In a region steeped in inter-generational jobs-for-life, châteaux were resorting to practices that might today seem normal – the paoching of staff. Jouet was outraged, writing that the practice took place ‘with no consideration for the good opinion of the neighbourhood’. French oak, essential for Bordeaux barriques, was needed to keep men from being swallowed by the quagmire of the trench, to build temporary bridges, and so on. Good luck buying iron for the barrels’ hoops. Régisseurs had to resort to the black market, and ‘careful logistics’, to acquire sulphur and copper sulphate needed to treat oidium and mildew, and often simply couldn’t get any. (The 1915 vintage was virtually written off due to a lack of these supplies). The 1918 at Château Latour was made using American oak staves (sacré bleu!) – all that Jouet could find, and at outrageous prices. Everything skyrocketed - between 1913 and 1919 the price of barriques rose 600%, other materials by 300% to 500%, and labour costs quadrupled. To make matters worse for the first growths the world’s war priorities tipped the market its head. Merchants found very little demand for the best wines. War France needed calories. Just calories, merci. Those who profited were the makers and merchants of the cheapest, drinkable vins ordinaires, be they French or from anywhere. (In a final irony, it was those who spent the war trading the basics that post-war had the capital to buy so many of these financially stretched top-tier châteaux). As costs spiraled upward the financial squeeze was further exacerbated by long-term contracts that fixed the price-per-volume between the châteaux and the merchants. In 1917, as the fate of Europe hung in the balance, Margaux, Mouton, Lafite, and Latour fixed for 5 years at 2650 francs per tonneau (900 litres). It looked right at that moment, but already by 1918 – finally – prices for the wines rose at a feverish rate. Château Haut-Brion, who fixed in 1907 for ten years, was able, in February 1918, to sell its 1916 at 5500 francs a tonneau. The first growths of the Médoc were shut out of these new profits and some indeed made losses.

Women unloading barrels during World War One, Bordeaux (National Library of France)

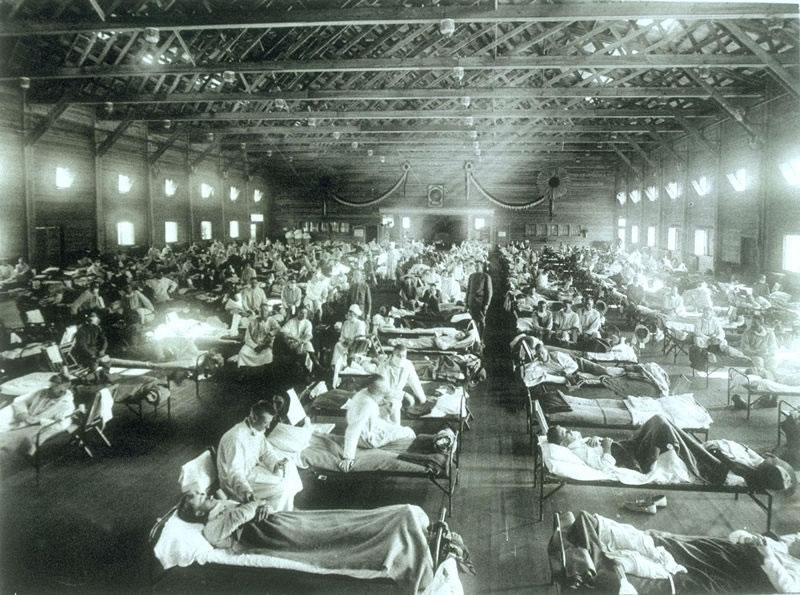

But the harvest of 1918 was to bear witness to not one but two tragedies. Even as the first grapes were gathered in late September, the collapse of the Central Powers had begun, with Bulgaria’s capitulation through the Armistice of Salonica on September 29th. October saw battles, routs, mutinies, and a series of further armistices, culminating in the one we remember best – on the eleventh hour or the eleventh day of the eleventh month – the Germans capitulated at Compiègne. But even as the end had come in sight, the whole world was deep in the grip of an epidemic so complete, so lethal, that we have not seen the likes of it since. About a third of the world’s population was infected by N1N1 influenza, and somewhere between 3% and 6% of the global population perished from it (Taubenberger & Morens 2006, Wikipedia). Lasting until December 1920, its peak frenzy was October 1918.

Soldiers from Fort Riley, Kansas, ill with Spanish influenza at a hospital ward at Camp Funston (US Army archives)

And yet the summer was beautiful, the grapes ripened, and the wine was made. In perhaps a final nod to the era that had now just ended, this was amongst the last of the vintages made from vineyards comprising both original (“pre-phylloxera”) vines and vines grafted onto American rootstocks. 1919 is the last vintage at Château Latour where this is the case. At Lafite it had been – apparently – 1917. That direct link between Bordeaux vine and Bordeaux soil bid its final farewell.

The reputation of the 1918 vintage has been mixed. Wine merchant Daniel Lawton, corresponding with Château Latour at the time is reported to have described the Latour’s 1918 in cask as ‘very healthy, but lacking the fullness that the drought must have absorbed, and the lees are bitter.’ André Simon, writing in 1945, describes 1918 as of ‘irregular quality; some fair wines. A few very good ones; many quite poor.’ Michael Broadbent MW, writing in 1991, described 1918 as having a ‘fine spring, warm summer, beneficial rain resulting in good end-of-war harvest early October. Healthy but rough. Can still be attractive.’ He gives most of the wines tasted during the 1980s ** to *** out of *****, though Haut-Brion ****, Léoville Poyferré ****, and Ausone **** were the best ‘18s he tasted. David Peppercorn MW (1982, 1991) puts the harvest commencement at 23rd September, and describes 1918 as

an average crop of very unequal quality. Maxwell Campbell described them as leathery. The erratic behavior of the vintage was typified for me in some Léoville-Las Cases tasted over the years at Loudenne. When first drunk in 1962, it seemed a little tired, but still hard and ungracious. The following year it seemed equally unsympathetic. However, in 1967 came a bottle with a gloriously perfumed bouquet far more typical of this growth, and with a lovely long, rich, harmonious flavour to match. The change was extraordinary.

Opening old wines, I have had similar experiences to these too. Of course a run of bad luck with corks and other issues can be to blame, but sometimes wines can blossom astonishingly late (or more than once, with dull, dormant periods in between).

But going into this dinner I had had little prior experience of 1918 Bordeaux. The most recent I had tasted was a bottle of 1918 Château Haut-Bailly that concluded a dinner The Fine Wine Experience hosted with Véronique Sanders in Hong Kong in January 2017. A century ago Haut-Bailly was ranked amongst the very elite estates of Bordeaux, with prices to match. So I was delighted, but not surprised to have found that wine vibrant, clear, fragrant and still fruity. It bore another curious element in its style. The owner, Frantz Malvezin had installed a fancy machine called the “Pastor” – a pasteurizing machine. Pasteurization – out of favour today, was a popular innovation of the day. It seems to somewhat ‘fix’ the wine. This ’18 Haut-Bailly experience had given me some hope for the five first growths tonight.

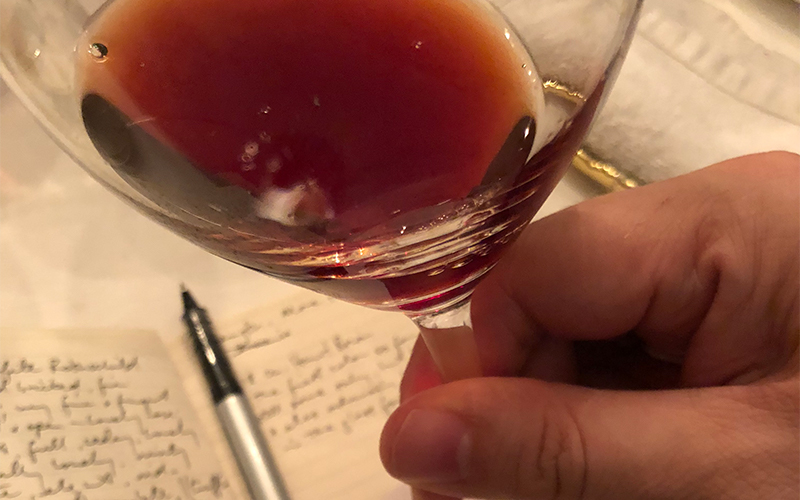

So, what did we find tonight, from these five noble sentinels, lined up straight on our table and in our glasses? What message would they have to whisper to us from a century ago? For the most part my tasting notes from these five bottles describe them as drinks – their colours, aromas, flavours, textures and so on. But it is more difficult to convey the experience, lest to say it was moving enough for me to feel the need to write all this about it! It’s impossible to fully understand a wine without knowing something of its context, some of which I’ve tried to provide here. But a forensic search in the glass for testimony of the vintage itself – the DNA in the story – is a challenge. A century we might think is an impossibly long telescope to reach through to the bubbling purple vats of October 1918 with its heavy veil of time. Nonetheless, the ungraceful heft and squareness of the 1918s, described decades ago, was still there to witness in our bottles of the Margaux and Mouton in particular. There is even evidence in the vanillin-tone of the Latour, a note I found curious until I discovered the wine’s secret – Jouet’s use of American oak, which always imparts a more obviously sweet tone than its French cousin. Was it Jouet’s wink to us tonight? In the Lafite and the Haut-Brion I experienced something of the happy surprise Peppercorn had found with his Las-Cases ‘18s in the 1960s, half a century ago. Perhaps it was their their solemn duty to ensure we remember them.

Although my preference is usually to open, smell, and then decant anything that smells ‘positive’ on opening, the consensus was to serve each of these wines immediately upon opening. I tried to hold back my share of each wine for as long as I could resist to note the changes in the glass – mostly positive, especially the Lafite which really blossomed after an hour in the glass.

1918 Château Lafite-Rothschild 95

Fine-aged bricked through appearance, a fine colour for age – brown, but still lively; from the first pour at 8.15pm this was fine and fragrant, sweet, open and lovely, and for the next hour it only improved. A minty note emerged; elegant on the palate, mid- to light in weight now, with complex flavours – wonderfully complex and soaring on the palate, with notes of earth, bacon, truffle and mint. By any measure a truly superb bottle of wine. So lovely in fact that I concluded – effuseively – ‘a testament to the greatness of Bordeaux’.

1918 Château Margaux 90

Fine bricked appearance, a little deeper in colour than the Lafite; an earthy sweet nose, not as clean as the Lafite; a sweet attack and then a touch metallic when served at 8.30pm – showing its age a little. More up front weight, but less length – more tannic in style. But by 9.45pm it was still in play and had developed more sweetness. Good.

1918 Château Haut-Brion 92

The finest colour of the five (pasteurized?), with still some ruby highlights amongst the tawny, admirably bright in the glass for its age; sweet with a really umami tone, mineral and stony, almost a hint of the sea, a touch of peat; fuller and more confident on the palate, silky, ripe and sweet with freshness of fruit and a Graves character of tobacco, cedar and what Michael Broadbent refers to as ‘hot tiles’ – a dusty mineral note. For its age this is pristine. Served at 8.45pm it was beginning to fade by 9.25pm with a light, less authoritative finish, fading with a warm glow. It was lovely while it shined.

1918 Château Mouton-Rothschild 89

A very fine full colour, bricked through with an amber-ochre edge to the rim; sweet on the nose – the sweetest – with a touch of Christmas cake fruits, but also a little sweaty with a note of confit onions, earth and some volatility on the nose; on the palate sweet and full, with more volatile acidity in the mix than the others so far, some balsamic vinegar. Kelly noted Chinese plums and yes, that was it exactly. Dries and then finishes abruptly. Crumpled with age a bit, but still an enjoyable glass of wine.

1918 Château Latour 88

The palest of the five (surprisingly), but still promisingly bright in the glass; at 9.10 when served, an initially odd sort of nose, a little varnishy – the smell of paint, but it grew sweeter after 30 minutes with a note of barley-sugar, or vanilla-fudge; much better on the palate right from the start however, with sweet fruit with the clearest curranty note of the flight, though there is high volatility now – indeed, it felt at home with the 1947 G. Conterno Monfortino that followed it at the dinner than the clarest that had just preceded it.